Filmed theater has its merits, the primary one being accessibility, but it seldom comes even close to matching the proximal experience of being there. Which makes David Mamet’s compelling screen version of his latest play, Henry Johnson, a curious anomaly. Rather than attempting to open out this characteristically talky, structurally stagey drama — four two-character scenes threaded together by narrative ellipses — the writer-director fully embraces the theatricality of the work. Reassembling the excellent cast from the low-profile 2023 premiere in Los Angeles, Mamet reels us in with some of his most trenchant writing in years.

Related Stories

To be clear, this is an actual movie, not to be confused with a live-capture quickie, in which cameras record a performance on stage. Real sets — a law firm office, a prison cell, the library at the same incarceration facility — replace a stripped-down, intimate staging in a black-box space. Beyond that, few concessions appear to have been made in the jump from one medium to another, and yet the modest, low-budget movie never feels stage-bound or static.

Henry Johnson

Cast: Evan Jonigkeit, Chris Bauer, Dominic Hoffman, Shia LaBeouf

Director-screenwriter: David Mamet

1 hour 25 minutes

There’s no expository padding and no enhancement of the narrative’s connective tissue, which we learn about but don’t see. Nor has either of the two crucial unseen characters been physically introduced. This is distilled Mamet, peeling back psychological layers and building characters exclusively through chiseled dialogue.

Despite the minimalist approach, the movie is surprisingly cinematic. DP Sing Howe Yam’s camera is attentive to every detail, Banner Gwin’s editing can be fluid or jagged, in sync with Mamet’s dialogue, and Jay Wadley’s score uses jittery percussion and pensive strings to great effect to heighten the tension. Most of all, the play is brought to life by a quartet of sharp actors fully inhabiting their roles — led by Mamet’s son-in-law Evan Jonigkeit in the title role, the only character who appears in all four scenes.

It’s hard to think of another dramatist of comparable stature to Mamet who has fallen so far out of critical favor since the early work that placed him — alongside Sam Shepard and August Wilson — among the most influential American playwrights of the 1970s and ‘80s. His tommy-gun dialogue, much of it laced with withering invective and punctuated with profanity, started a shift in the language of both theater and movies in this country.

Mamet’s disfavor arguably has less to do with his hard-right turn into neocon bloviation than the calcification of much of his more recent writing. Dissections of power and masculinity that once bristled with adversarial vitality evolved into arid dialectics and windy anecdotes pickled in smug cynicism and lacking in thematic clarity.

That makes it a pleasure to be reminded, in Henry Johnson’s attention-grabbing opening, of Mamet at the peak of his considerable powers. A casual conversation between work colleagues that’s gradually revealed to be a wily interrogation, the scene puts Henry in the office of his senior law firm associate Mr. Barnes (seasoned Mamet pro Chris Bauer, in spectacular form). They discuss an old college friend Henry has recommended for a job.

It emerges that the unnamed friend has done time for manslaughter, accepting a plea deal to avoid a first-degree murder trial. Barnes plays along, maintaining a vaguely detached manner, but he clearly knows more than his questions let on. The details of the crime are vicious, involving a girlfriend who refused to terminate an inconvenient pregnancy, and an involuntary abortion induced with violence.

But Barnes is already aware of the facts and more interested in the college friend’s hold over Henry. The younger man concedes that he always admired his buddy’s success with women, seeming naively unaware of how bad that makes him look when he’s talking about a murderer and rapist. While coolly informing Henry that he knows the full extent of his illegalities on the friend’s behalf, Barnes tells him he has been groomed since college, kept on a string until such time as he might prove useful to his friend.

The brilliant economy of that extended duologue makes it virtually a perfect Mamet one-act — a conversation that becomes a simmering pressure-cooker in which a master manipulator remains offstage (or off-camera in this case) while a person with power mercilessly exposes his subordinate as a dupe.

Henry is an easy mark, a patsy. But Mamet and Jonigkeit give him a fascinating opacity. Is he merely prey, so lacking in character that he invites the imprint of more confident men, subconsciously finding ways to excuse even their most heinous sins? Or does he have the sketchy morality of a knowing participant?

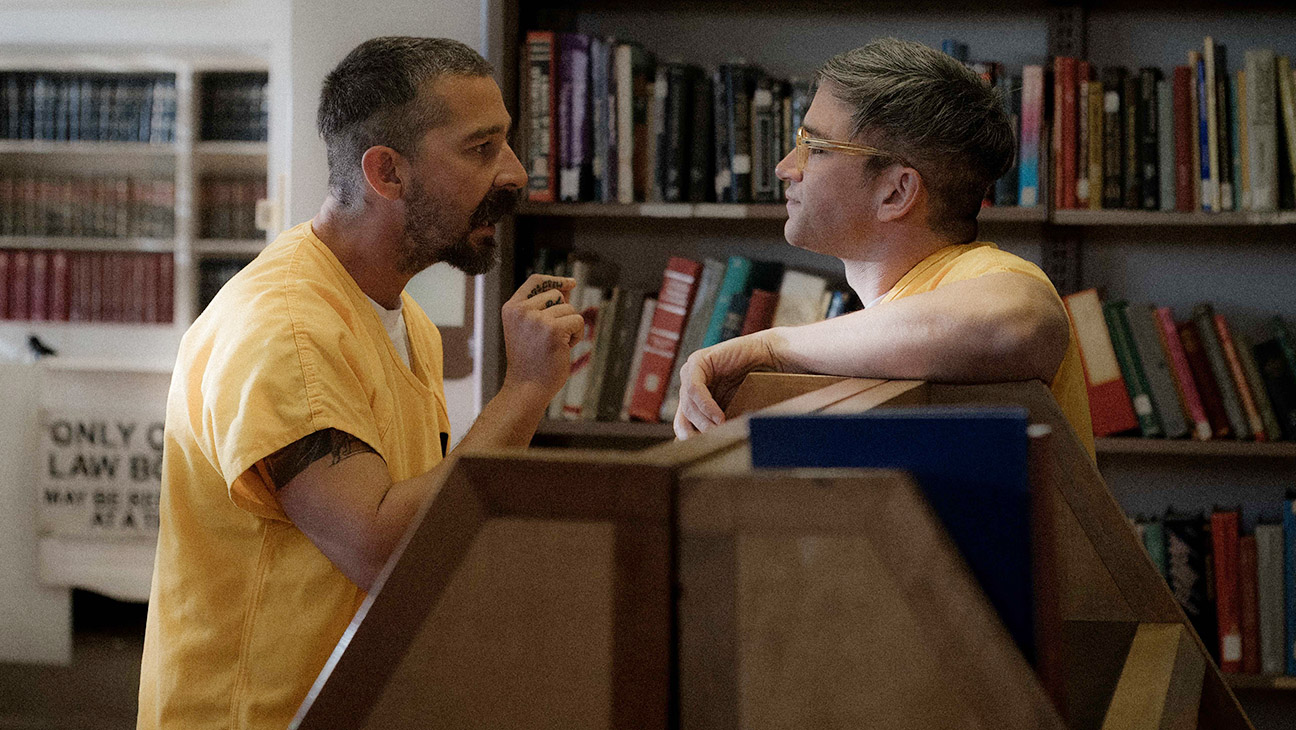

Those questions keep bouncing around as the scene shifts to Henry’s first day in prison. His cellmate, Gene, is played by Shia LaBeouf as a kind of charismatic mesmerist, able to get what he wants out of the guards just as surely as he can out of Henry. The edgy unpredictability, the hint of madness and lurking danger that adrenalize so many of the actor’s best performances — on occasion offscreen as well as on — make him ideal casting for Gene, who comes on like a feverish manosphere motivational speaker.

One of the things that makes LaBeouf’s performance so exciting is the way Gene keeps us — and Henry — guessing about whether he’s taking the newbie under his wing or setting him up for subjugation. Jonigkeit plays much of the scene as if hypnotized by his cellmate’s nonstop stream of words. When Gene schools him not to contend with the strong in the prison yard but to stick with the weak who want to be taken advantage of, is he offering Henry advice or slyly assessing where the white-collar criminal sits in the ecosystem?

That ambiguity continues some weeks later in the library, where Gene has arranged for Henry to be assigned as a worker. In the interim, Henry has been seeing the prison counselor, a woman who is the drama’s other major unseen character. Also in the meantime, Henry’s charges have been upgraded; he is now being considered an accessory to murder.

The scene seems designed to provoke — perhaps deliberately playing into the charges of misogyny that have often been leveled at Mamet — as Gene dismantles Henry’s reasons to trust the counselor.

He questions why she chose to share confidences with him about her own shady past. “She’s courting you,” Gene tells him, which is not all that different from his views on the friend who landed Henry in prison: “You’re his punk.” With a Svengali-like sense of purpose, Gene suggests that Henry put the counselor’s trustworthiness to the test, artfully construing a way to get their hands on a gun.

The fourth and final scene again jumps forward by an unspecified amount of time to find Henry armed and barricaded in the library with wounded prison guard Jerry (Dominic Hoffman) as his hostage. The weary guard is subtler than other characters at pulling Henry’s strings, but Jerry needles his captor by surmising correctly that even his list of demands is Gene’s work.

As with the earlier advances in the action, Mamet shows consummate skill at scattering clues that allow us to piece together each new development.

Accompanied by the sounds of the prison alarm, or of police cars and later a chopper outside, Jerry talks about changes in the job over the years, sharing stories from the past. But is he, like everyone else, playing Henry for a chump?

Adopting an unconventional release model, the movie will be available for rental starting May 9, directly from its official site (https://henryjohnsonmovie.com), with nationwide theatrical screenings beginning the same date in Los Angeles.

It’s been 10 years since a new Mamet play was produced in New York (his 1985 Pulitzer Prize for Drama winner, Glengarry Glen Ross, is currently running on Broadway) and 18 years since he last directed feature. This pithy screen adaptation was conceived as a record of the play’s original L.A. production, but it stands confidently as a film in its own right. At a time when the world seems increasingly divided into winners and losers, exploiters and suckers, Henry Johnson speaks with sardonic eloquence to our current moment in American life.

Full credits

Cast: Evan Jonigkeit, Chris Bauer, Dominic Hoffman, Shia LaBeouf

Director-screenwriter: David Mamet

Producers: Lije Sarki, Evan Jonigkeit

Executive producers: Peter Baxter, Marcel Bonn-Miller, Sheldon Stone

Director of photography: Sing Howe Yam

Production designer: Gabrael Wilson

Costume designer: Laura Bauer

Music: Jay Wadley

Editor: Banner Gwin

Sound designer: Justin M. Davey

1 hour 25 minutes

THR Newsletters

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day